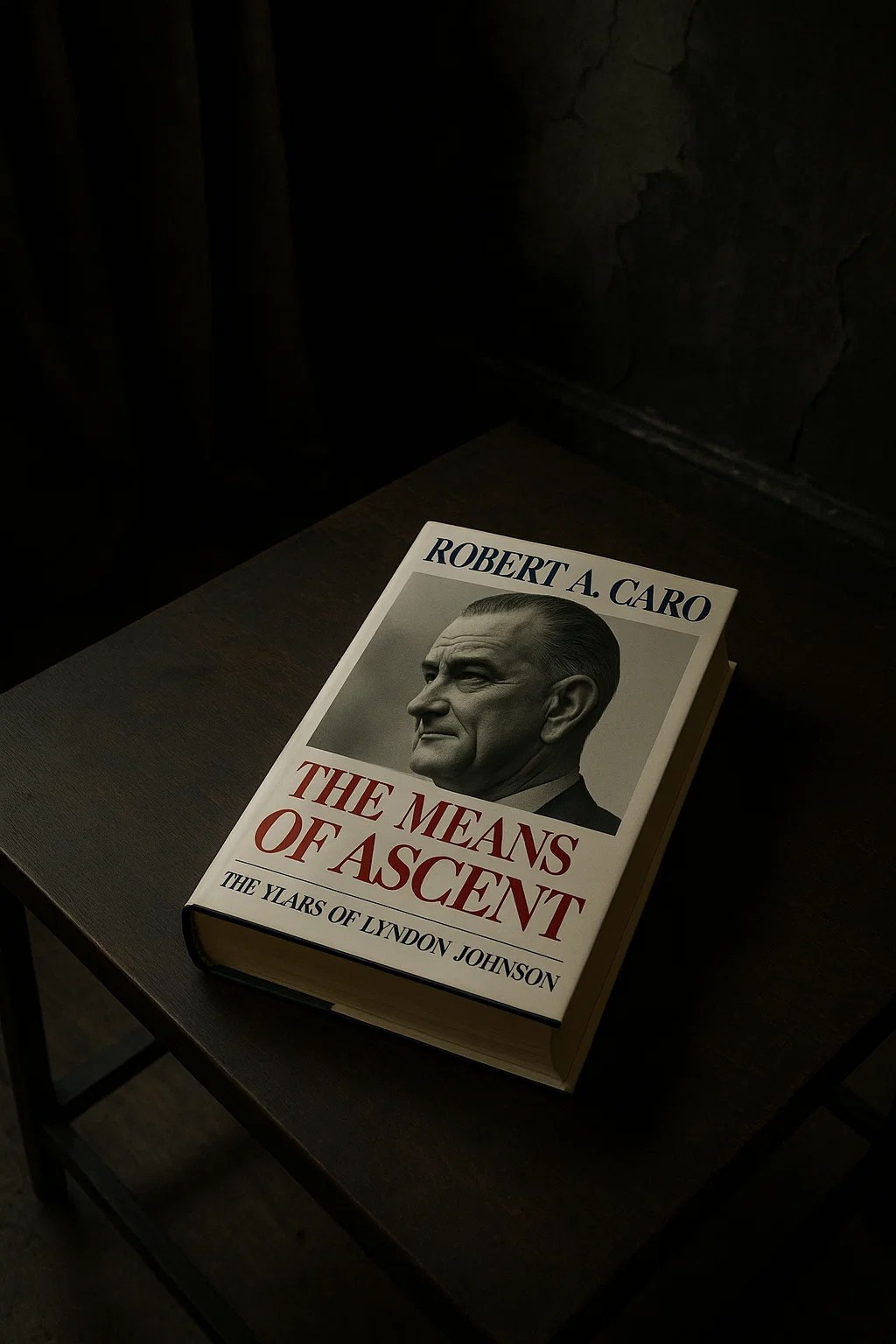

The Means of Ascent, the second volume in Robert Caro’s epic biography of Lyndon B. Johnson, covers a seemingly narrow slice of history—the years between LBJ’s failed 1941 Senate bid and his infamous victory in the 1948 Texas Senate race. But this short stretch of time is foundational for understanding the man Johnson would become. While The Path to Power showed us the ambitious striver from the Hill Country, this volume reveals the blueprint of a political machine built on deception, patronage, and ruthless pragmatism.

For most of the seven years between campaigns, Johnson did almost nothing of consequence in Congress. Instead, he focused on accumulating the one thing he lacked: MONEY. What stands out is how he accomplished this—not through hard work or smart investments or post-war economic tailwinds, but by weaponizing his political connections to manipulate government regulation.

The genesis of his eventual empire is the acquisition of KTBC, a small radio station in Austin, which he purchased in his wife Lady Bird’s name. At the time, the station was struggling due to limited signal range, inconvenient broadcast hours, and a conjested frequency. But Johnson, leveraging his ties to the Federal Communications Commission, managed to secure a frequency change and expanded broadcast hours. It should be noted at the time, the FCC was under attack, and by acting as their sponsor in congress, he has immense sway. The turnaround for KTBC was swift and lucrative. What had been a weak station suddenly had a monopoly on prime-time radio in a rapidly growing state. It was, by Caro’s account, the moment LBJ became financially independent and it happened entirely through political manipulation.

The Steal

But the heart of this volume, and the most damning section, is Caro’s exhaustive investigation into the 1948 Senate race. Caro, as always, is methodical in his research and unrelenting in his attention to detail. The campaign pitted Johnson against former Governor Coke Stevenson, a man Caro portrays as principled, austere, and deeply respected. AKA everything Johnson was not. Stevenson, though less dynamic, was a self-made figure who believed deeply in the democratic process.

A core element of the race was that Johnson had the power of the purse and was willing to use it. With that money, he brought modern campaigning to Texas. He traveled by helicopter, allowing him to crisscross the vast state quickly and efficiently. He blanketed the airwaves with messaging, much of it misleading or outright false, confident that his opponents wouldn’t have the ability to respond. One of his most effective tactics was launching false attacks on Stevenson’s record. Claims that Stevenson was slow to support FDR or that he had voted against veterans’ pensions. These accusations were untrue, but Johnson knew that in politics, the first blow is often what sticks.

Still, none of this, however unethical, matched the corruption that defined the election’s final days. The vote was razor-close. Stevenson had the early lead. Then, votes from rural counties in the Rio Grande Valley trickled in, days late and suspiciously lopsided. In precinct after precinct, Johnson posted improbably high margins. In one now-infamous case, 202 ballots were added to the total. Suspiciously, these “votes” were in alphabetical order, all written in the same handwriting, and all for Johnson. These votes, added at the eleventh hour, gave him an 87-vote margin of victory.

Here is were Caros research pays dividends. He interviews eyewitnesses, combs through court transcripts, and retraces the legal maneuvering Johnson employed to stop Stevenson from getting a full investigation. The result is one of the most painstakingly documented accounts of electoral theft in American political history. Johnson not only stole the election, but he also used every legal and institutional tool available to cement the theft and silence dissent. Even The U.S. Supreme Court was harnessed to to defraud voters!

Reading these passages, I found myself viscerally uncomfortable. Yes from the fraud but because of the pride Johnson took in his tactics after the fact. He spoke of the 1948 race as his finest political achievement. He wore the “Landslide Lyndon” nickname, originally coined in mockery, as a badge of honor.

Legacy of a Man

Caro’s achievement here is helping us see how these years shaped Johnson’s later career. Everything that came later from the Civil Rights Act, the Great Society, and Vietnam was rooted in the lessons Johnson internalized during this time: power is everything, truth is flexible, and winning is the only thing that matters.

Its hard to know where to stand when we know what comes next. Johnson would go on to sign some of the most transformative legislation in American history. He would lift millions out of poverty, expand voting rights, and reshape the American social contract. And yet, the foundation of that power was built on lies, manipulation, and stolen votes. We truly have to as does the good he accomplished later in life redeem the way he climbed to power? I’m not sure.

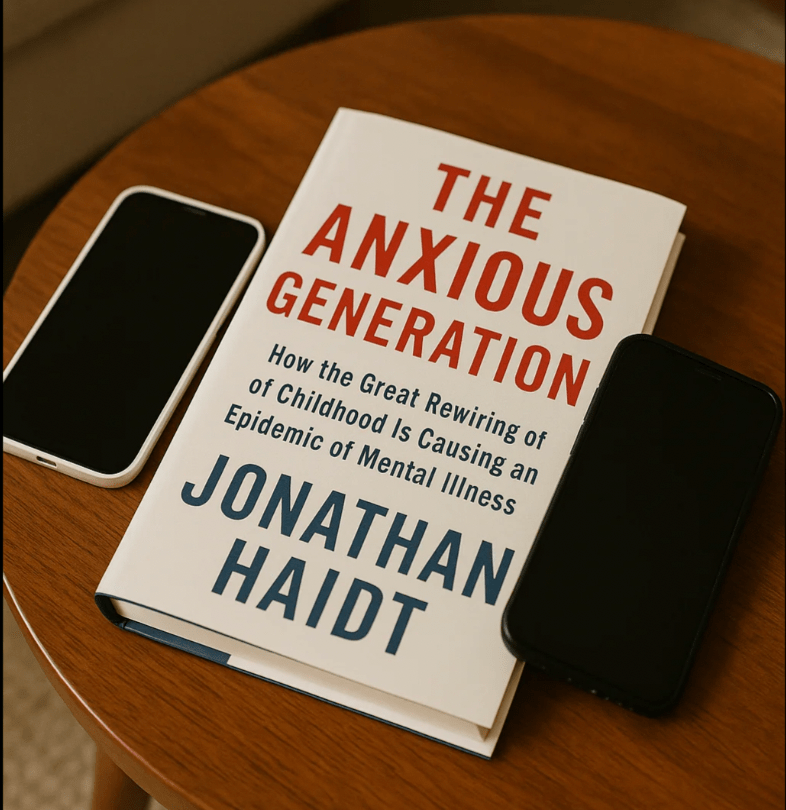

This volume is essential reading for anyone interested in American political history, not just because of what it says about Johnson, but because of what it reveals about the broader system. Institutions can be bent. Rules can be worked around. And in the hands of someone as relentless and unprincipled as Lyndon Johnson, democracy itself can be manipulated to the point of farce. While I hope we would have learned from this history, but it seems we are in the middle of the modern day reincarnation, except with no to little improvements to The United States.

Leave a comment